CAMELS FOR SALE: PUSHKAR

by Margaret Deefholts

|

|

|

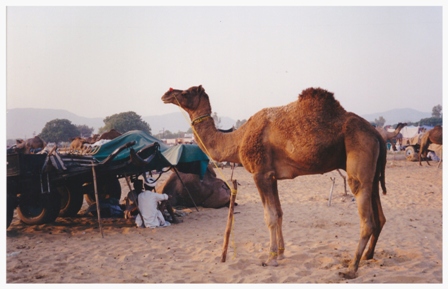

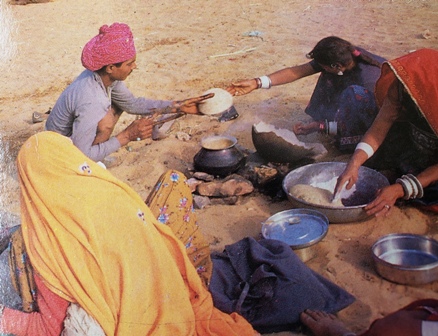

The sands of the Rajasthan desert glow dusty gold in the sunset. Smoke from campfires turns the scene into a smudged shadow play of silhouetted turbans, camel humps and tents. The evening is redolent with the smell of dung, burning wood and spices—and the sounds of horses whickering, the belching snort of camels and the tinkling of silver anklets.

I am in Pushkar, one of over 200,000 visitors—pilgrims, tribal herdsmen, tourists, performers and traders of camels, cattle and horses—as the town celebrates Rajasthan's largest and most exuberant festival.

|

|

Set within the folds of the Aravalli hills, Pushkar is a tranquil little village for most of the year. But at Kirti Purnama (the new moon) around early November each year Pushkar blazes into activity. All because a god's wife went into a royal snit.

Eons ago, Brahma the god of creation was cruising around on his celestial swan, scattering lotus petals and looking for a special site for his abode on earth. One of the petals fell at Pushkar and formed a lake. The Creator was thrilled. It was the perfect spot. Priests bustled around, the sacrificial fire was lit, and everything was set to go. But, Brahma's consort Savitri hadn't turned up. The yin-yang (male-female) wholeness was crucial to the rites. Worse still, the configuration of the stars had to be just so, and the auspicious hour was zipping by all too quickly. Brahma fumed. The priests frantically produced a young milkmaid, Gayetri from the congregation. “A spouse, any spouse, will do,” they urged, so Brahma agreed and the ceremony commenced.

Well, when Savitri arrived there was hell to pay. She'd been selecting her outfit, putting on her make-up, chatting with the wives of other gods, comparing notes on hair styles and so on. A goddess can't be expected to rush that sort of thing. And who the heck was this Gayetri dame, anyway? Infuriated beyond measure, Savitri promptly put a hex on Brahma. Pushkar would be the only place in the length and breadth of India that would worship him—and that too, just for four scant days every year. Then she stormed off and immolated herself on a nearby hill which is marked today by a temple. And Pushkar is still the only site—probably in the world—dedicated to the worship of Brahma.

Early the following morning, I make my way to Pushkar Lake. This is the mainstage for the festival's exaltation of the mighty Creator. In the pre-dawn light, the sky is a pearl-grey, but to the east the horizon is streaked flamingo-pink. I squeeze through a shifting mass of pilgrims, tourists, camera-crews and foreign journalists, to the water's edge, where groups of saffron-robed priests face the rising sun as they chant hymns to the accompaniment of drums and wailing conch-shells. A disembodied voice blares through a loudspeaker, warning people to keep an eye on their possessions and their children, and not to crowd together too closely. Canute talking to the waves. Nobody pays the slightest attention.

Women, fully clothed, sit immersed in the shallows, floating their offerings of marigold garlands on the lake's surface. Men scoop the sacred waters into their hands and chant mantras , as they lift their cupped palms to the heavens. They then reverently drink the water which is reputed to have miraculous spiritual and physical healing powers. Sadhus with matted dreadlocks and tridents at hand sit in the lotus position on the banks; some ascetics are entirely naked, except for grey ash smeared over their faces, hair and bodies. The sun rears up over the Lake, like an enormous blood-orange, and in an hour's time, the scrubland of the surrounding desert turns the colour of burnt umber.

|

|

|

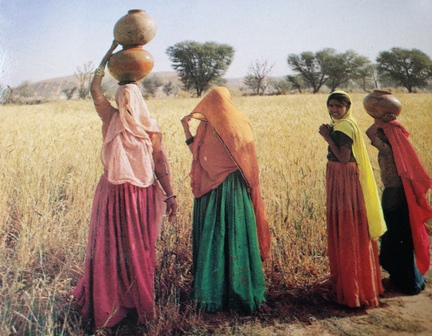

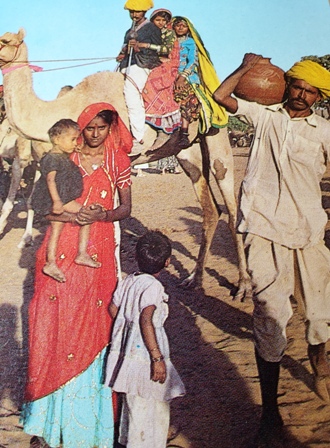

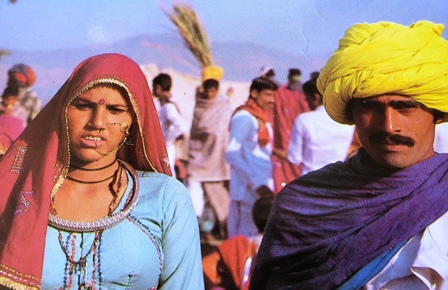

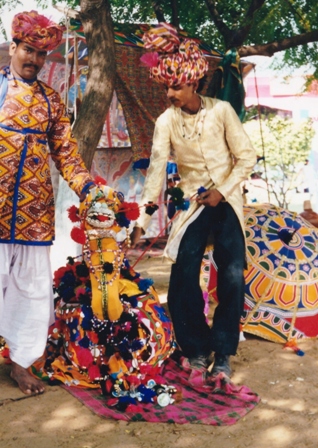

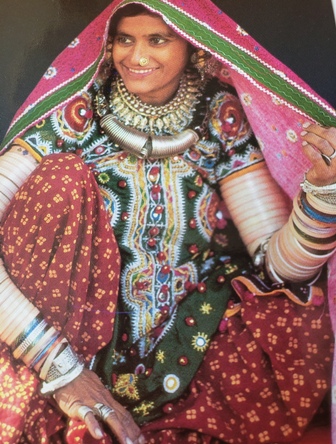

Later in the day, I shoulder my way through the narrow lanes of Pushkar towards the fair-grounds. The scene assaults the senses. Village women float like shoals of butterflies, dressed in shimmering peacock blue, iridescent green gauzy veils and hot pink and scarlet skirts, their necks, arms and ears bedecked in silver filigree jewellery. Sidewalk vendors sell a gaudy cornucopia of wares: bangles, perfumes, embroidered cloth shoes and even tasselled horse-saddles. Brightly caparisoned camels pick their way through the crowds drawing carts mounted with effigies of Brahma and his consort, amicably seated on swans. Loudspeakers blare film music. Cows, their horns painted and hides daubed with colour are led along and people throw coins to their owners. Puppeteers enthral audiences with traditional music and stories. Hawkers sell balloons twisted into shapes of gods and demons, and strolling musicians, play their stringed instruments. The noise and confusion is both chaotic and exhilarating.

At the racing arena, camels and horses are being readied for competitions. A young man wearing a T-shirt with “Hard Rock Cafe” printed across the front, sits near me and strikes up a conversation. He introduces himself as Jaisingh Rathor, and goes on to explain that the horses, now lining up at the far end of the field, are unique to Rajasthan. Bred by the princely family of Jodhpur originally for the polo-field, they are now an intrinsic part of India's cavalry regiments. They are small, tough, and have inward-twisted ears as their distinguishing feature. He watches curiously as I film the camel parade: the animals lope in a circle, like a merry-go-round, their heads tightly reigned in to control their pace and direction. They gradually pick up speed, urged on by cheers from the crowd. As I lower my video camera, Jaisingh asks whether I'd like to meet a camel breeder and trader.

|

|

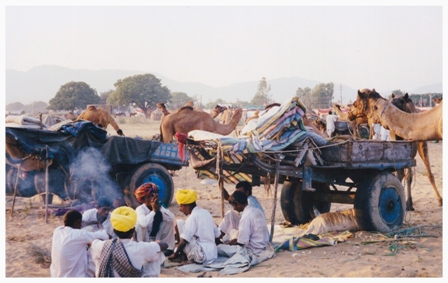

I follow him to an area behind the show grounds. Under the fierce afternoon sunlight, a group of men wearing intricately woven turbans of orange and yellow, sit on their haunches smoking beedies. I wait while Jaisingh chats to one of them. The man rises to his feet and ambles over to me. “This is Balsingh” says Jaisingh, “he is a Gujaar, a tribal herdsman and camel breeder. I will translate for you, if you wish to ask him any questions.'

Balsingh has a moustache which lies like curled parentheses on each side of his strong, arched nostrils. He wears baggy pants, and a purple mirror-work embroidered vest over his loose-sleeved cotton kurta. He grins amiably at me, his teeth very white against his weathered skin. I ask him how old he is.

Balsingh's eyes gleam. “Twenty-five.” he says. Jaswant Singh breaks into laughter. Balsingh is forty-five if he's a day.

“How old are you?” Balsingh asks.

“I'm fifty-seven,” I say.

Balsingh stares at me. “Never!” he says, “You look, at the most thirty-five!”

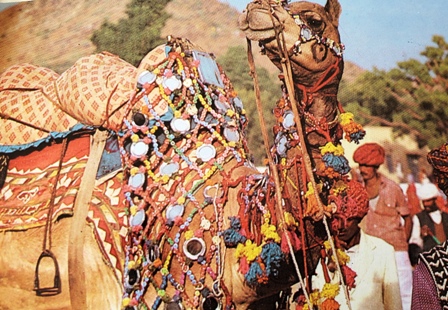

With that piece of outrageous blarney, Balsingh goes on to claim that his camels have won first prize in Pushkar's camel racing competitions for the last ten years. That he has sold four this year and has made fifty-five thousand rupees on the deal, and even better, he's bought four young camels at a bargain price of only fifteen thousand rupees for the lot “Beautiful animals, nice teeth and skin. See, there they are.” The camels gaily decorated with bunting and silver-thread embroidered saddles regard me with hauteur. “Would you like to ride one?” he asks. “Usually I charge Rs. 300 for fifteen minutes...but for you, free!”

It turns out that Balsingh has also just arranged a highly desirable match for his eldest son. With another camel dealer. Part of the dowry is forty camels, he says. Jaisingh interprets this straight-faced, but his eyes are dancing with suppressed mirth. Balsingh pauses to regard me speculatively. Would I like to come to his village and spend some time in his house? He has fifty acres of pastureland, (camels are expensive to feed, he says) and a house that has twenty-five rooms...lots of space. I make non-committal noises. Balsingh takes this to mean I need reassuring. He tells me that a young American woman spent a whole month in his house three years ago. She still writes to him, but he can't read English. “She was a ‘special' friend” he adds with a wink at Jaisingh. If I like the idea he'd be happy to have me as a “special” friend too.

I ask him what his wife thought of this arrangement. He shrugs. “Why don't you ask her? She's sitting there.” He points to a group of women sitting under an acacia tree. “Gossiping as usual with her friends”. His wife is shy, and pulls her sari over her head, cups her hands over her mouth, glances sideways at the other women and giggles. “She says to ask you to please take a picture of her?” Jaisingh says. So while the women, huddle together beaming, I click my camera at them. “Don't forget to send us a copy, “ says Balsingh. He hands Jaisingh a rumpled piece of paper and commands him to write down the address of his village.

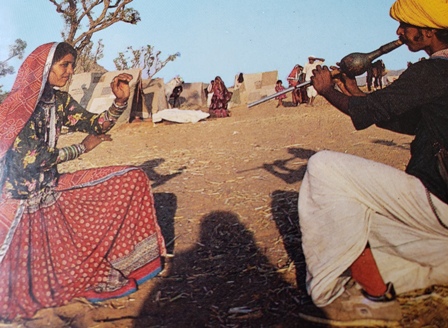

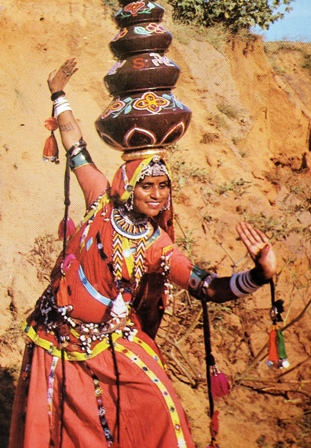

The gypsies are said to have originated in Rajasthan, having migrated from here and spread through Hungary, Romania, Italy and Spain. The rhythm of castinets, the riffs on stringed instruments, and the passionate love songs and laments, as played by a group of musicians on the lawns of our campsite, are all reminiscent of gypsy music. The dancers are extravangantly dressed: the women flash embroidered mirror work in the swirl of their skirts, and the men with peacock blue and pink turbans, hip-strut as they drum their feet to the beat of a tabla. The dance troupe re-enacts the pagentry and drama of ancient Rajasthani myths and legends, and a woman balancing five earthenware pots stacked one above the other, dips and sways in a traditional village folk dance.

I leave Pushkar with regret. It has been an amazing four days, with a crowding of colour, movement and myth and legend, all brought together in a rambunctious festival. An experience that is unforgettable. And after all, how often does one get propositioned by a roguish camel dealer.